ISF (insulin sensitivity factor) is an unusual and widely misunderstood part of T1D management. It’s very rare that we should be using an ISF with no other adjustments. But most people use their ISF automatically every time they need to correct high blood sugar numbers. Then we wonder why we’re experiencing stubborn high blood sugars for hours and hours. So, let’s break it down. What is ISF? How is it calculated? And most importantly, when should you use it?

I am not a doctor or medical professional. This article is for informational purposes only. If you are thinking about changing the way you treat your diabetes, consult your medical team for assistance.

What is ISF?

ISF is one of a handful of basic calculations that a person with T1D has to do to figure out their insulin doses. There are several names for this calculation. It’s most commonly called insulin sensitivity factor, correction factor, or ISF.

Your ISF is a number that represents how much one unit of insulin will lower your blood sugar level.

It varies from person to person. For an individual, it also varies based on time of day, activity level, and several other factors. It will also change over time. Your ISF is quite the moving target. That’s why it’s good to put it to the test every now and again.

The purpose of ISF

When your blood sugar level is higher than you’d like, your ISF is used to calculate how much insulin should bring that number back into range. It’s a number, and more often than not, a fairly useless one.

A correctly calculated ISF will only truly work when there are no other factors at play. Yet, most people use it regardless of the situation and other factors. This is the first misconception about insulin sensitivity.

How does it work?

I’ll use an imaginary person to explain it. “Annie” has T1D.

Let’s say Annie has a blood glucose target is 5.0 mmol/L (90 mg/dL). That’s what she wants her blood glucose to be all the time. But, that’s not reality. Sometimes, Annie’s blood glucose level goes high.

She checks her blood glucose level and finds that it’s at 12.0 mmol/L (216 mg/dL). If she wants to bring that number down to her target, her ISF tells her how many points 1 unit of insulin will lower her blood glucose number.

Let’s say Annie’s ISF is 4 mmol/L (72 mg/dL). That means, for every unit of insulin that Annie injects (or pumps), her blood glucose will come down by 4 mmol/L (72 mg/dL).

Here’s the equation:

mmol/L: (12.0 – 5.0) ÷ 4 = ?

OR

mg/dL: (216 – 90) ÷ 72 = ?

First, you take the current blood glucose level and subtract the target blood glucose level. That gives you how many points you need to correct for. In this case, she wants to bring her blood glucose level down 7.0 mmol/L (126 mg/dL) points.

Then, take that number and divide by the ISF. mmol/L: 7.0 ÷ 4 = 1.75 OR mg/dL: 126 ÷ 72 = 1.75

Based on Annie’s ISF, she needs 1.75 units of insulin to bring her blood glucose level back down to her target.

That’s how ISF works… in theory.

In the real world

Annie doesn’t live in a bubble. Her blood glucose is fluctuating constantly. Each insulin dose wears off after 2-4 hours. She waits until the previous dose has worn off to prevent stacking insulin (I’ll talk about how that term is getting very outdated another time).

So, 3 hours after dinner, Annie checks her blood glucose and finds it’s up to 12.0. She uses her ISF to correct it. It should take 1.75 units, right?

But, Annie’s dinner contained fat and protein. Those macros take several hours to convert to glucose in our bodies. Her blood glucose of 12 is still going up. The protein from her food is still digesting and the fat is making her more insulin resistant. Her dinner insulin dose has worn off, but the food from dinner is still affecting her blood glucose level. Unfortunately, she hasn’t factored that in.

When she gives herself the 1.75 units for her current blood sugar level, it doesn’t bring that number back down to her target. Instead, it only counters the fat and protein rise and her blood glucose stays around 12.0 for the next 3 hours. It might even go up further than 12.0.

This might continue throughout the night. Her blood glucose number finally comes back into range in the early morning hours, after 3 or 4 corrections. She was high for 7, 8, 9+ hours during the night.

Now Annie is starting to think that her ISF is not working. Maybe instead of 4 (72), it should drop to 3 (54), or maybe even 2 (36). So, frustrated by the prolonged high during the night, Annie adjusts her ISF.

But then

Annie has increased the amount of insulin she uses to correct high blood sugar levels. Maybe she even doubled it, based on her observations.

And why wouldn’t she? That’s how the doctors taught her to do it.

But now, when Annie wakes up in the early morning hours and her blood glucose is high, she will use her new ISF to correct it.

Except, this time, there is no fat and protein to counteract the extra insulin. This time, her correction will drop her dangerously low.

Does this sound familiar?

Giving correction after correction and having your blood glucose number barely budge at all?

Adjusting your ISF only to have your glucose level drop suddenly the next time you give a correction?

It’s frustrating. It seems like you’re on the T1D roller coaster and no matter what you do, you can’t get off the ride.

I remember my son’s doctor asking us if there was a pattern. On nights with highs, did we eat higher-carb meals? I never saw a pattern. Of course, I was looking at the wrong things. Frankly, so was she.

It’s not the carbs that cause these prolonged highs to happen. It’s the protein and fat.

Protein takes approximately 5 hours to digest. A large portion of it gets converted into glucose in our bodies. But, the insulin has worn off by then. Glucose is entering our bloodstream and there’s no insulin to take care of it. So, our blood glucose level goes up and up and up.

Fat causes insulin resistance. That means it will take more insulin to cover a protein and fat rise. A small percentage of fat also converts to glucose in our bodies. It can take 10-12 hours for that to happen. The insulin is long gone by then.

Using your ISF to combat this is like using your ISF when you sit down to eat a meal. It’s not going to work.

It doesn’t take much either. Only a few grams of protein or fat for most people. And if you think about those timelines, it’s almost always a food rise that you’re tackling.

That said, some people run their basal insulin quite heavy and that covers the p/f rise. That is… IF they eat the same amounts of protein and fat all the time.

How to figure out your ISF

If adjusting it based on previous situations doesn’t work, how are you supposed to know what your ISF is?

It’s very similar to basal testing.

You need to create a situation where there are no other factors at play. You’ll see how rarely this actually happens when I explain it.

- Activity level: Activity increases our insulin sensitivity. So to get an accurate ISF, you have to test it on a day where you’ve had an average day. If you’ve been extra active or extra sedentary, the test won’t work properly. Activity affects insulin sensitivity for 24+ hours after the activity is done. Remember, things like vacuuming the house count just as much as going for a run.

- Food: Ideally, if you’re able to completely fast, that will give the most accurate results. An ISF test needs to be done about 8-10 hours after your last meal or snack. Protein continues to digest for approximately 3-5 hours and fat tends to cause insulin resistance. This means, if you have even a little bit of those in your system while trying to calculate your ISF, it will skew the results.

- Blood glucose level: This one can be a bit frustrating. Usually, we want to stay in a certain range. To test your ISF, you have to have elevated blood glucose. You can’t test a correction factor if you don’t need a correction.

- Basal HAS to be accurate: If you don’t have your basal dialed in, meaning it keeps bg steady in the absense of food, activity, and bolus insulin, then you can’t properly test anything else. Basal is the foundation of T1D management. If your basal is pulling bg up or down, or it’s covering food in some way, you won’t ever be able to get an accurate ISF.

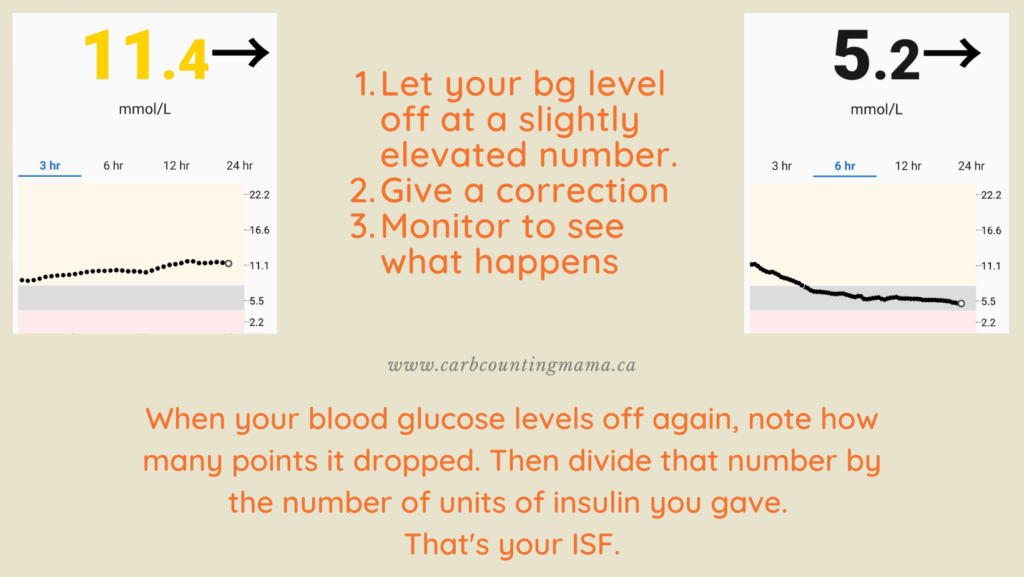

Now you’re set! Simply let your bg level off at a slightly elevated number, give a correction (based on your previous experience or current ISF), and monitor to see what happens.

When your bg levels off again, note how many points it dropped. Then divide that by the number of units of insulin you gave. That’s your ISF.

Related: Basal Testing: The Beginner’s Guide

The above image is from my son’s graphs.

I gave 1.5 units to bring down that blood glucose of 11.4.

Here’s the equation:

11.4 – 5.2 = 6.2

6.2 ÷ 1.5 = 4.1

His ISF at that time was approximately 4.1 (approximately 74).

But, when will we actually use his ISF?

It is extremely rare to have a high blood glucose level with no other factors.

- There is almost always food digesting in our bodies. That’s not what ISF is for.

- Activity makes most people more sensitive to insulin.

- Fat makes most people insulin resistant.

- Medications have an impact on insulin sensitivity and insulin resistance.

- Hormones cause insulin sensitivity and insulin resistance.

- Illness affects insulin sensitivity.

This means it’s very difficult to test how accurate your sensitivity factor is. It’s always changing.

And, even if you know for sure that it’s accurate, there are very few scenarios where you’d use that equation by itself and it would work how it’s supposed to.

That’s why Annie’s ISF didn’t work for her

Because Annie doesn’t live in a bubble.

None of us do.

There are constantly other factors affecting the blood glucose level of a person with T1D.

This is, in part, why many of us are on the bg roller coaster. We’re using formulas that are fixed. They’re meant for perfect scenarios.

They need to be fluid. Because we are rarely in those exact scenarios that the formulas were built for.

So yes, test your ISF

But also, learn how to dose for fat and protein. Understand the role of basal insulin and how to test it.

Realize that our lives are constantly changing. Our bodies are constantly changing. The factors that affect our T1D are constantly changing.

Pay attention. Learn to recognize when those formulas will benefit you and when they won’t. Use them as a guide and figure out when and how to make adjustments.

It is possible to get off of the T1D roller coaster. But we can’t just leap off. It takes a lot of work, a lot of observation, and a community of people who can help guide you.

It’s great that you want to understand ISF. I hope this article explained it. But for an equation that almost everyone in the T1D world uses, it’s almost never useful.

~ Leah

For more tips and stories about T1D, join the Carb Counting Mama email list, and make sure to head over to the Carb Counting Mama Facebook page and “like” it.

Leave a Reply