Last weekend was our youngest son’s 5th birthday party. We went to an indoor play place, had pizza and ice cream cake, and lots of fun with friends. All of this and more could send our older son’s blood sugar levels into a roller coaster of massive spikes and dips. We can throw our hands up and go along with the ride. Or, we can learn more and try our best to tame the roller coaster.

Disclaimer: I am not a doctor or medical professional of any kind. I do not and will not give medical advice. What I talk about in this article and on this website is for informational purposes. Talk to your diabetes team if you’re thinking about changing part of your diabetes management.

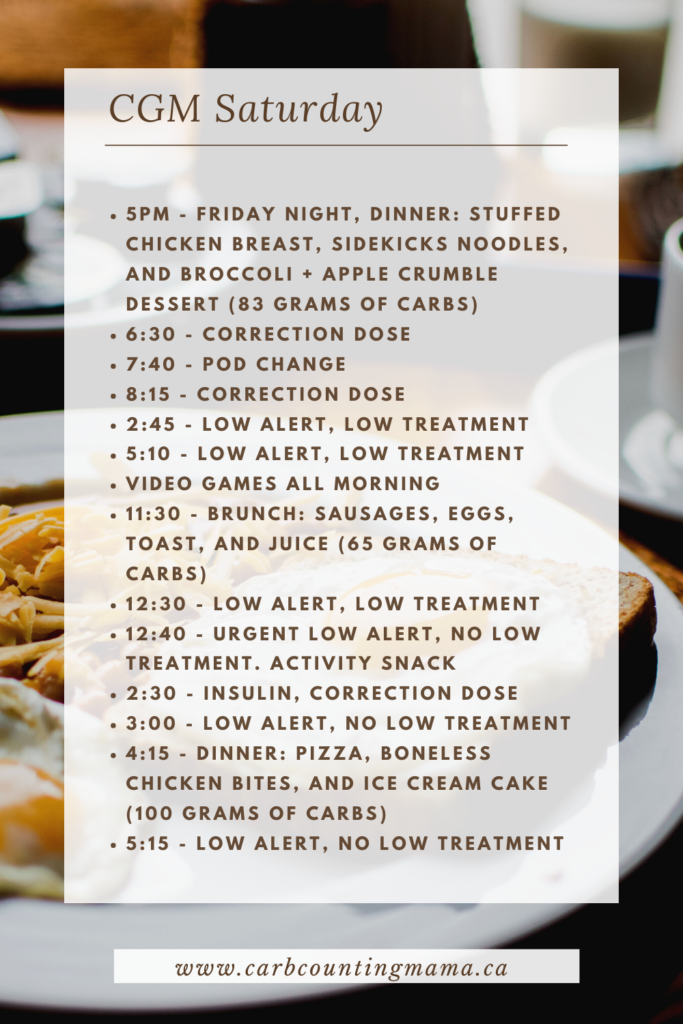

Let’s take a look at our day

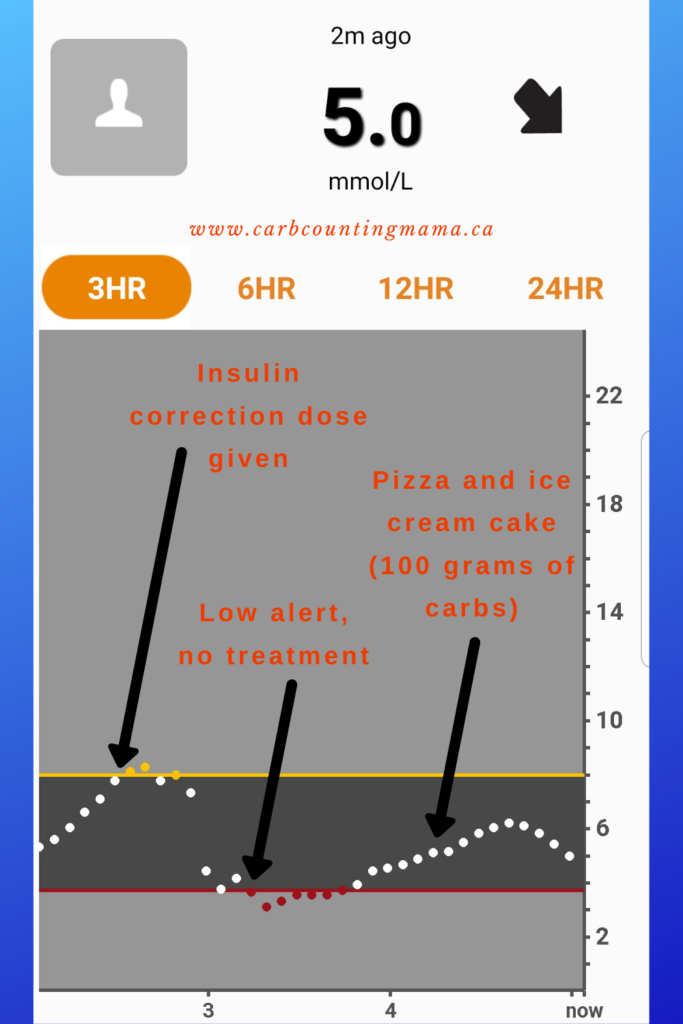

This is all of the food eaten, interventions taken, and alerts from 5 PM on Friday to 7 PM on Saturday. It’s also notable that we were at an indoor playground from 1-3 PM on Saturday.

The graphs for that time frame can be seen below.

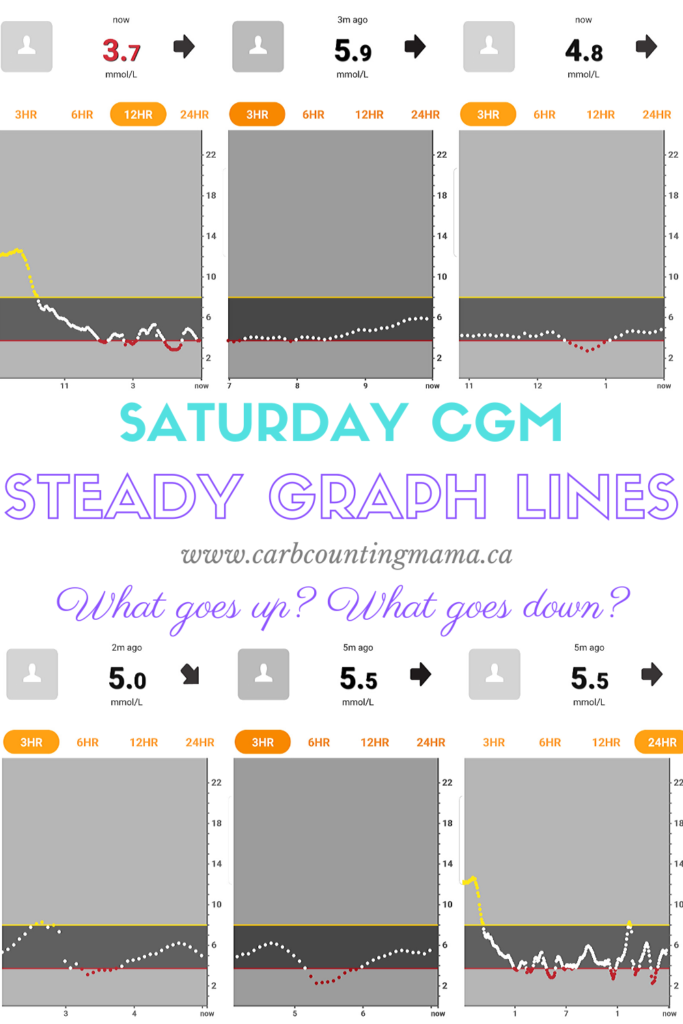

Our graphs:

** Numbers are in mmol/L. To get the mg/dL equivalent, take the number I used and multiply by 18 **

The high alarm on these graphs is set to 8.0 mmol/L (144 mg/dL) and the low alarm is set to 3.7 mmol/L (67 mg/dL). Jordan’s low alarm on his phone is higher. I have mine lower to give him a chance to treat his own lows before I intervene.

In order, these graphs are:

- 7:00 AM, 12-hour graph

- 10:00 AM, 3-hour graph

- 2 PM, 3-hour graph (I got distracted, it was supposed to be 1:00 PM, oops)

- 5:00 PM, 3-hour graph

- 7:00 PM, 3-hour graph

- 7:00 PM, 24-hour graph

I will say that every time you see red on that graph, we did a finger poke to confirm. The lowest number we got by finger poke was 3.7. So, the red looks a lot scarier than it actually was.

Feel free to match up what happened on the graphs with the actions we took during the day. I’m going to go into more detail about the 4th graph in a bit. But first, let’s go over the main culprits that cause blood glucose levels to go up and down.

What makes blood sugar go up?

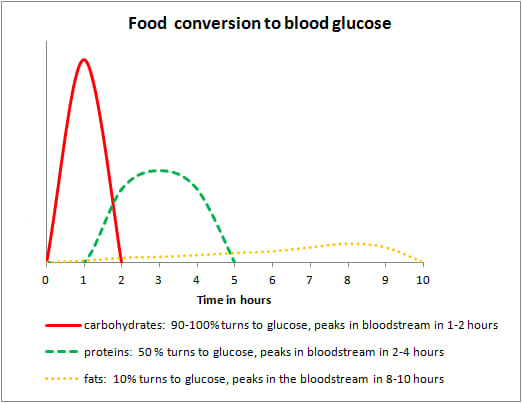

The major factor for increased blood sugar is food. Not just sugar. Not just carbs. All macros make blood sugar go up.

Simple, refined sugars:

Things like juice, gummies, honey… anything you’d use to quickly treat a low blood sugar. These are “quick in, quick out”, meaning, they spike your blood sugar and leave your system almost as quickly as they enter it. If you bolus for this type of food, you shouldn’t see a spike hours later.

Complex carbs:

Rice, pasta, cereal. Something that is high in carbs, but low in fat and protein. These are actually also “quick in, quick out” if they’re eaten by themselves and are not high in other macros (protein and fat). Not as quick as the simple sugars, but they don’t last for hours on end either.

Protein:

High protein snacks and meals also spike blood sugar. It’s a longer, less severe spike, as protein takes longer to digest. Approximately 50% of protein converts to glucose in our bodies. But, it takes several hours.

Fat:

Foods that are high in fat can be the most difficult to deal with. Think: pizza, fast food, Chinese take out. These guys keep messing with your blood sugar level for 8-10 hours after eating them. Most insulins used for food bolusing are only effective for a maximum of 4 hours. It’s not surprising that they can cause problems with hyperglycemia.

What makes blood sugar go down?

Insulin:

Nothing will ever replace insulin. In people without diabetes, our bodies are constantly regulating our blood sugar levels with insulin. When you have T1D, you have to do it yourself.

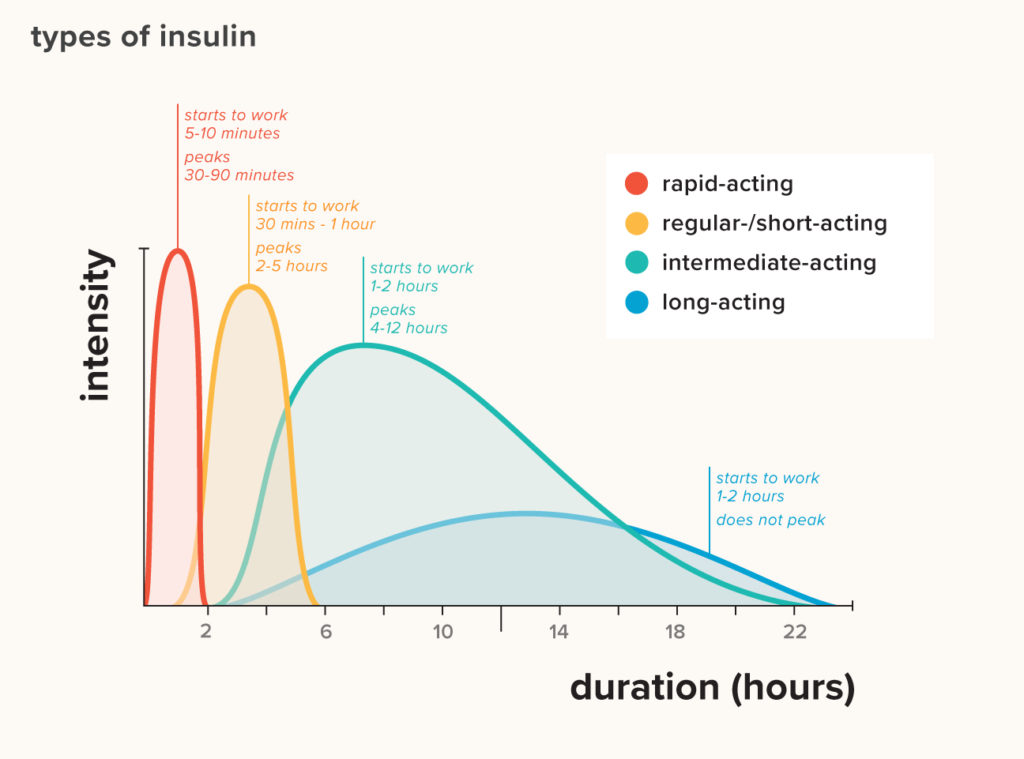

Basal insulin. This is the long-acting or background insulin that you take to keep your blood sugar levels stable in the absence of food or lots of activity. If your basal dose is accurate, you should be able to fast without your blood sugar level climbing or dropping very much.

Bolus. A bolus is the insulin given to cover food. Generally, people with T1D use an insulin to carb ratio (or ICR) to calculate how much is needed for meals and snacks. The ICR is individual and varies greatly from person to person.

Correction. A correction dose is given between meals if your blood sugar level is too high. The insulin sensitivity factor (or ISF) is used to calculate a correction dose of insulin. Like the ICR, the ISF varies from person to person.

As with macros, different types of insulin have different active duration times:

Activity:

Sports, running, even playing at a playground. Any activity can cause blood sugar numbers to go down. This is particularly true if there is insulin on board (IOB). That is when insulin is still active in the person’s body from their last bolus or correction dose.

There are a few reasons why activity lowers blood sugar numbers. For one thing, your body is burning energy. That is glycogen from the muscles. Then, the body replenishes its glycogen stores from glucose in the bloodstream, lowering blood glucose levels. Secondly, the burning of glycogen makes the person more sensitive to insulin. That means they can use less insulin during activity and it will still be effective.

Certain kinds of activity will raise blood glucose levels. But, until you know which is which, it’s safer to assume it will cause a drop in numbers when you’re active.

Hot baths/ showers:

Many people with diabetes are warned against hot tubs, hot baths, and hot showers. The reason? These things can cause unexpected hypoglycemic episodes.

The heat from the water causes the blood vessels in the skin to dilate, which, in turn, makes the insulin absorb more easily.

It’s generally recommended to avoid hot baths/ showers for an hour after injecting insulin. The heat may cause insulin to work too well and cause low blood sugar. Which can be particularly concerning in a shower or bathtub if you suddenly faint or have a seizure.

That said, a hot bath or shower can be very helpful if you’re having trouble getting a high blood glucose number down. Having a bath after doing a correction dose may be just what you need for that stubborn high.

Using this knowledge to make decisions

Yes, many many things affect blood sugar. But, the above items are what make up the majority of roller coaster numbers. Things like hormones and illness contribute to changes in insulin resistance and insulin sensitivity as well, but they don’t, in themselves, cause spikes and dips.

If we focus on the things we can really take charge of, we can get off of the scary monster roller coaster and tame it, little by little.

So, we know the main things that cause blood sugar levels to go up and down. And we know the rough timing of how it all plays out. So, with the help of a CGM, why couldn’t we look ahead at what we’re about to do and eat, and look behind at what might still be affecting the blood sugar level, and use that information to dose more proactively rather than reactively?

It’s not just luck

The diabetes Gods didn’t decide to go easy on us because it was a special day. Diabetes didn’t play nice. Diabetes did exactly what it does. But we knew what it would do (mostly) and we planned accordingly.

There are only 3 notable things that happened during this graph. But that’s not all that we look at to make decisions.

The correction dose

His blood glucose started drifting up right around 2:00. I corrected it around 2:30. At the time, his blood glucose level was 7.9 and rising. If we didn’t have a CGM, I wouldn’t have given any insulin.

If I didn’t know about how protein and fat works in the body, I wouldn’t have given any insulin. But I did.

He was running around at a play place. I could have said, “Oh, he’s going up from excitement.” But I didn’t, because he wasn’t.

Everything pointed to not giving a correction dose. So, why did I give insulin?

3 hours prior to this rise, he had eaten sausage, eggs, and toast for brunch. 3 hours. The perfect amount of time for the bolus of insulin to wear off, but not the food. That high protein and fat meal is still digesting in his system. Part of it is still converting to glucose.

I did not use his ISF to calculate this correction. This is a food rise.

Unfortunately, there is no set calculation to figure out how to dose for fat and protein. It’s mostly trial and error. However, there are a few methods you could use as a starting point here.

I had to look at what was pushing his line up (his brunch mostly) and what was pushing it down (activity) and decide if they’d cancel each other out or not. I decided the brunch would push up more than the activity would push down, so, I gave him insulin.

Glancing and follow up

I don’t wait for alerts. I glance at my Dexcom Follow app frequently. Catching a high or low before it alerts is way easier than dealing with them when they’re already out of control.

You may have noticed that steep drop in the graph. Believe me, I noticed it too. When I glanced at the graph, and it said 4.4 ⬇️⬇️, I thought maybe I had given him too much insulin.

But we did a finger poke and he was at 5.2. Dexcom evened out over the next few readings and I did a second finger poke just to be sure, 5.3.

It wasn’t too much insulin after all. It not only evened out with no intervention, but it started rising again, likely still due to the protein and fat content in the brunch. This time, I decided the activity and IOB would counter the rise. Besides, we were going to be eating again very soon.

Early dinner

We ate very early because of the birthday party. Dinner was at 4:15. You can see in the graphs that the pizza and ice cream cake didn’t spike him. In fact, we probably should have delayed the bolus a bit or split it differently. He dipped down into the red again around 5:00.

To be honest, I’m fairly certain his basal is too heavy and it helped out with the high protein and fat meals we had during the day. I’m going to be doing more basal testing to figure that out.

Taming the roller coaster

Was our graph perfect? Of course not.

Was it better than the last birthday party? Yes.

Were there spikes and dips? Yes, several. But, they weren’t as big as they would have been if we had just dosed and moved on. And, next time, there will be even less.

There is a lot to learn when it comes to T1D. After years and years of dealing with the disease, we still learn something new every day.

But sometimes, things aren’t as complex as we think. Sometimes, it can help a lot to go back to the basics: food, activity, and insulin.

It’s not easy by any means, but focusing on these things first can make troubleshooting a lot more straightforward. And you might notice that more spikes and dips are caused by meals than you realized.

Happy carb counting!

~ Leah

Do you dose for protein and fat? How do you go about doing it? Let me know in the comments!

For more tips and stories about T1D, join the Carb Counting Mama email list, and make sure to head over to the Carb Counting Mama Facebook page and “like” it.

Leave a Reply