I was out with a friend running errands. By the time we were done, it was close to lunchtime. We zipped through a drive-thru and to grab a quick lunch for ourselves and the kids. We got back to my house and gave everyone their food. Then, out came my “diabetes logbook” and I started writing and looking things up on my phone. It’s so automatic for me that I didn’t realize how unusual this T1D math looks to people who don’t do it every day. My friend commented, “Woah, there’s a lot of math going on over there!”

This friend has been there since the beginning

I’ve known her since before my son was diagnosed with T1D. The concept isn’t new to her. She’s been at gatherings and birthday parties with us when we’ve done this math. But she didn’t realize how much we actually do until that moment.

It’s been almost 10 years of T1D for us. And, up until recently, we mostly guessed at things. We’d SWAG Jordan’s meals and he had an insulin pump for several years. An insulin pump does a significant portion of the math for you. I’ll get into why we don’t SWAG anymore in a bit.

Now, he’s MDI and we’ve been keeping track of everything.

We’ve always done fine with his diabetes. His numbers have never been a concern to his diabetes team. He’s never had a seizure or lost consciousness. We’ve never had to use glucagon. He’s never been in DKA.

But, he was still often on the T1D rollercoaster, so we’ve been working on that lately. Keeping track of everything helps a lot.

I’ve talked to this friend about what we do, but she had never seen it.

If my good friends, who I constantly talk to about T1D management, don’t understand what we do on a regular basis, I guess a lot of people wouldn’t understand. So, I figured I’d break it down for everyone who doesn’t live in the world of T1D.

Here’s what we had for dinner the other night

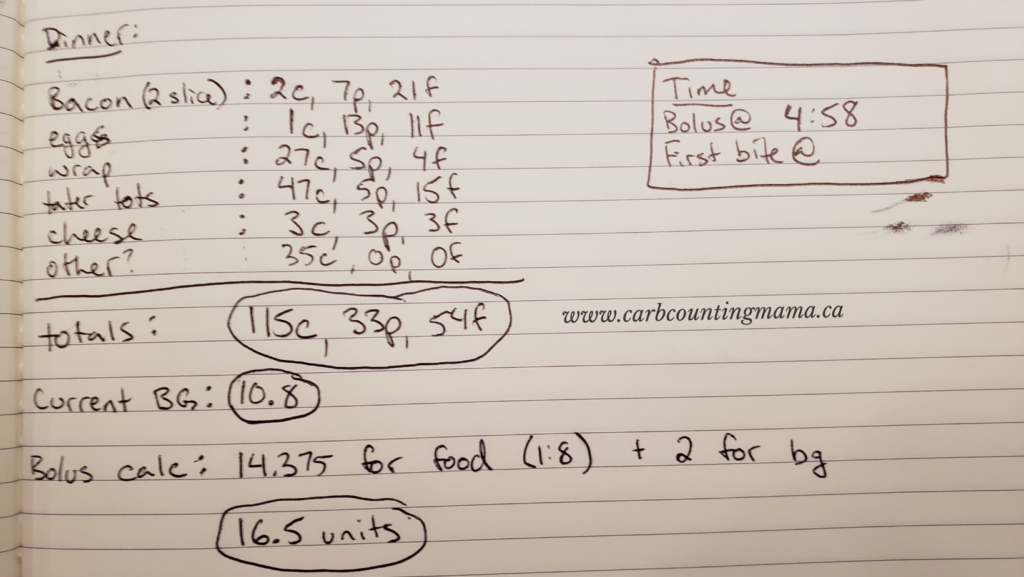

I apologize for my messy writing. I wasn’t planning on sharing this when I wrote it. Although, I’m sure even if it was printed neatly it would look like a mess to most people. So, I’m going to explain it.

We had breakfast wraps and tater tots for dinner. Most people would simply make their wrap, load up their plate, and they’re good to go. Dinner is served!

But that’s not how it works in our house.

What is he eating?

First, I break down what we are eating for the meal. The amount of insulin he needs is dependant on how many grams of carbs he’s going to be eating. So, I need to know what’s in everything that he eats.

Sometimes I know the amount before the meal, sometimes I have to figure it out on the spot while he’s filling his plate. Often, it’s a bit of both.

I broke down what Jordan was going to eat: 2 slices of bacon, 2(ish) scrambled eggs, a tortilla (that’s the “wrap” on the list), an unknown amount of tater tots, a slice of cheese, and “other” (condiments, sauces, or anything else he might add once the food is on the table).

I made that list while making dinner. For this particular meal, I knew the amounts that he was going to eat for most of it, so that was helpful.

A bit of subtraction

Almost everyone with T1D counts carbs. Most people use net carbs. That means, you take the total carb amount and subtract the fiber (and most sugar alcohols in foods that contain those). That’s because our bodies don’t process fiber and sugar alcohols, so adding them into your carb count could cause you to give too much insulin.

Many people who are more advanced with their T1D management also keep track of protein and fat. A large part of protein converts to glucose in our system. That means more insulin. Fat often causes insulin resistance, which means even more insulin.

That’s what the columns are. C for carbs, P for protein, and F for fat.

A few of the items on the list were very simple.

The bacon, eggs, wrap, and cheese (we use singles cheese slices for our wraps) are all straight off of the nutritional labels. The serving sizes are exactly what he was going to be eating. Perfect.

Simply grab the carb amount from the label and subtract the fiber. That takes care of our carb counts. Protein and fat are even easier. No subtraction required.

The tater tots on the other hand…

Cross-multiplication

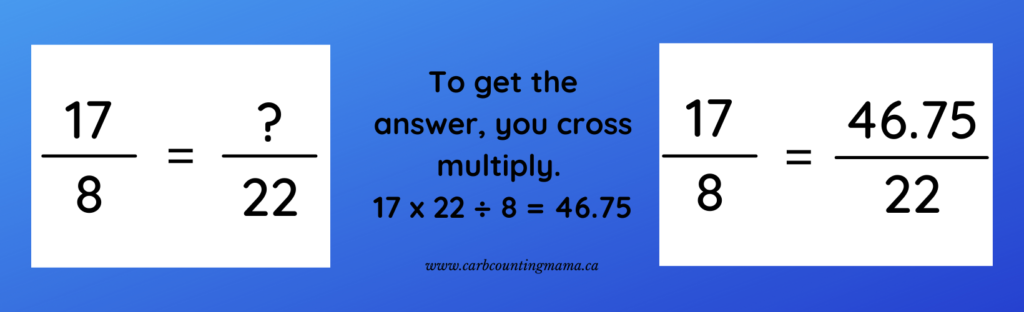

There’s a lot of cross multiplication involved in T1D math. If you have a nutrition label, but you want a different amount than the serving size, you cross multiply to get the correct carb, protein, and fat amounts.

I had to do this with the tater tots. The serving size was 8 tater tots (85g).

That serving size has 20g of carbs with 3g of fiber. So 17g of net carbs. But he didn’t take 8 tater tots, he took 22.

There are 17 grams of net carbs in 8 tater tots. But Jordan wants 22 tater tots. How many grams of carbs are in 22 tater tots? Sounds like a word problem right out of a math textbook doesn’t it?

This can be done with either the amount of food, eg: 8 tater tots vs 22 tater tots, or with the weight of your food.

Did I mention that there’s a lot of rounding in T1D math? While it’s technically 46.75 grams of carbs, we just called it 47 because seriously, it’s complicated enough without adding in decimals… yet.

“Other” ended up being sriracha and bbq sauce. Add those together and we’ve got the “other” line completed.

That’s the top left corner of the notepad. With a little subtraction, addition, and cross-multiplication, we’ve figured out all of the macros in his meal.

This was an easy meal. There was no food scale, food app, or unknown factors. Imagine trying to figure out something like chili or homemade treats.

The insulin equation:

Most people who have T1D do this equation to figure out how much insulin they need when they eat. Some have an insulin pump or an app that does some of the math for them. Some do it in their heads. Most wouldn’t even recognize this equation. But this is the mathematical formula for insulin dosing.

Remember BEDMAS from school? The order of operations. Brackets, exponents, divide/multiply, add/subtract. Every time we have to give insulin, whether we realize it or not, this is the formula that we need to solve.

Most people don’t think about T1D math like this. They just do it. This formula is one of the most basic versions. There’s more to it than this. Unfortunately, the rest is not just math. A lot of it is intuition.

Which makes starting with the correct information that much more important.

The terms and acronyms

“BG” and “T”

“BG” means current blood glucose level. “T” is the target glucose level. If the person’s current glucose level is higher than their target, it needs to be corrected (brought back down into range). If this part of the equation results in a negative number, that means one of two things. Either you can skip that portion of the equation, or you have to treat your low blood glucose before eating.

ISF

ISF is the person’s insulin sensitivity factor. This is how many points 1 unit of insulin will bring down the person’s glucose level. Speaking of T1D math, this number is individual and varies a lot from person to person. Your ISF changes frequently and should be tested regularly.

IOB

Insulin on board is one of the most important things in T1D math. Insulin, once in your system, is active for 2-4 hours. IOB tells you how much of your previous bolus is still active. You always need to dose for new carbs, but if you have IOB from a previous correction, you don’t want to correct BG again with new insulin. If you do, it compounds the insulin and can cause low blood sugar levels.

Net carbs…

This is what we’ve already figured out. Everything we’ve done up to this point? That was just to figure out what number we need to plunk into “net carbs”. We personally also keep track of the protein and fat, but that’s not used for this equation. We use those later on.

Sometimes figuring out net carbs is simple, sometimes it takes a fair amount of calculation.

This is honestly the part that I hate the most. It takes a lot of time and effort sometimes.

We used to SWAG everything that my son ate (SWAG = Scientific wild ass guess). We’d look at his plate and estimate how many grams of carbs were in his food. Lots of people think that they’re good at SWAGging. I was one of those people up until recently. But really, unless you have the same thing over and over, chances are you’re not that great at it.

During Diabetes Awareness Month every year, I share a post asking people to SWAG a picture of a simple restaurant meal. A burger and yam fries. According to the nutritional information from the restaurant, the total carbs in the meal is 110 grams and the net carb amount is 100 grams.

The majority of people SWAG the meal around 60 grams. These are people who live with T1D and do this 24/7. When my son ate that meal, I did the same thing.

No wonder so many of us in the T1D community have “unexplained” blood glucose numbers. We aren’t even starting with the correct numbers for our calculations.

ICR

ICR is similar to ISF. This is the person’s insulin to carb ratio. It tells you how many carbs 1 unit of insulin will cover. Like ISF, ICR varies from person to person. It often is different at different times of day as well. Most people need more insulin for breakfast than they do for other meals later in the day.

It’s also a moving target. We are taught to set an ICR (or multiple ICRs) and use them exclusively when doing bolus calculations. But it doesn’t really work like that. You’ll see what I mean when we get to that part of the equation.

Bolus

I’ve used this word several times already. And it’s in the equation. A bolus is an insulin injection. Whether you’re giving insulin via syringe, pen, or pump. Whether it’s to cover food or to bring down a high bg. A dose of insulin is called a bolus.

Related: What is a Bolus? The What, Why, and How of Insulin Dosing

Back to my chicken scratch T1D math

We’ve done the math to figure out what Jordan is going to be eating. The total net carbs was 115. Now we need the other information.

The correction:

This is the first part of the equation. We’re figuring out how much insulin is needed (if any) for the current blood glucose level.

Subtract the target blood glucose number from the current blood glucose number, then divide that number by the ISF.

We need his current bg for that. That’s easy. Either look at the number on the CGM/FGM or do a quick finger poke. We usually use the number on Jordan’s dexcom. Going into that particular meal, his glucose level was 10.8 mmol/L (195 mg/dL).

Normally, I don’t like him eating when his blood sugar is already on the high side. But life happens.

His ISF at the time was approximately 4 mmol/L (72 mg/dL). His target is 5.0 mmol/L (90 mg/dL). So, reasonably, he should have gotten around 1.5 units of insulin for that glucose number. Here’s the math:

10.8 – 5 = 5.8

5.8 ÷ 4 = 1.45 units.

If T1D math worked the same as regular math, 1.45 units of insulin should land him nicely at 5.0 mmol/L (90 mg/dL).

You might have noticed that we gave 2 units for his bg. T1D math isn’t exact. There are factors that we can’t really put into an equation. I didn’t note it in the logbook, but his bg was still going up at the time. So, I added a bit of insulin to help with that.

This is where IOB would be subtracted. Some people subtract it from the final number. We rarely subtract it at all. There wasn’t any IOB in his system at that time anyway. One less thing to worry about.

The food:

Take the number of grams of carbs being ingested and use the insulin to carb ratio to figure out the insulin amount.

He was eating 115 grams of carbs for that meal. Now, most people use a set carb ratio to calculate the insulin dose. We don’t.

This is where the macro profile (protein and fat) comes in.

In general, Jordan uses an ICR of 1:8. That means he needs one unit of insulin for every 8 grams of carbs that he eats. If the food is “carb-heavy”, but fairly low on fat and protein, like candy or cereal, he needs a lower ratio. We might use a 1:6 ratio for that kind of food. This particular meal was quite high in all 3 macros.

Another factor that we look at is his activity level. Activity causes insulin sensitivity. That means the more active he is, the less insulin he’ll need for the same meal. When he’s very active, sometimes he needs a 1:10 ratio instead of the 1:8. Again, that wasn’t the case with this meal.

After quickly assessing those things, we went with his usual 1:8 ratio. Here’s that math:

115 ÷ 8 = 14.375 units.

Adding and rounding

So, we’ve ended up with 1.45 units for the bg level and 14.375 units for the food. This is why I didn’t want to get into decimals when we calculated the net carbs earlier. It just gets too complicated.

The total insulin amount that we’ve calculated is 15.825.

Since Jordan uses insulin pens, we can only do full units or half units of insulin. So, we have to round that number up or down. We almost always round up. It’s easier to catch a low with a few grams of carbs (like a starburst candy) than giving more insulin for a high later on.

Based on what his blood sugar was doing, and the macros of the meal, we rounded up and added another half unit.

16.5 units.

Don’t worry about the Time in the upper right corner

That’s just to keep track of how long his pre-bolus was and to keep track of when we should be expecting a rise from the protein and fat.

For different meals, you need to give insulin more or less time to start working. It’s like a race between insulin and food. You want them to end in a tie. So often you need to give the insulin a head start. That’s what a pre-bolus is. Dosing 5, 10, 20 minutes before you start eating.

Around the 2-4 hour mark, that 16.5 units of insulin is wearing off. But his body is still digesting that food. It’s still converting a lot of that protein into glucose in his body. So, after a couple of hours, we’ll probably have to give more insulin for that.

But let’s keep it simple. That’s a discussion for another time.

We do all of that for everything that my son eats

Yes, we could SWAG his food and it would be a lot faster and easier. But the T1D roller coaster is more likely when we do that.

So, we use nutritional labels, a food scale, and My Fitness Pal.

Yes, an insulin pump or a diabetes app will do a lot of the other T1D math for you. But our insulin sensitivity is constantly changing due to outside factors and the apps simply can’t take that into account.

So, our meals include addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, BEDMAS, ratios, factors, fractions, rounding, and decimals.

And my friend, we do all of that T1D math in less time than it took you to read this article.

No wonder people with T1D are so smart!

… and exhausted.

~ Leah

Did you know that T1D involves so much math? Most people don’t. How much of this was surprising to you? Let’s chat about it in the comments!

For more tips and stories about T1D, join the Carb Counting Mama email list, and make sure to head over to the Carb Counting Mama Facebook page and “like” it.

your articles are always so incredibly helpful. thank you for being there for all of us parents/grandparents and others who are coping with t1d either daily or sporadically. you didn’t mention the nighttime fun. I don’t think most t1d parents have had a good night’s sleep since their child/children were diagnosed unless they got a break from some loving grandparents or others. thanks again for all you do for our community.