We all know that Dr. Banting discovered insulin. He, along with his team Charles Best, John Macleod, and James Collip worked together to make that discovery 100 years ago. We celebrate Dr. Banting’s birthday as “World Diabetes Day” on November 14th. But how did he make his discovery? Let me tell you a bit about the dogs of diabetes.

(This post contains affiliate links)

** CONTENT WARNING **

This article is about the role that dogs played in the discovery of insulin. Animals were harmed to achieve this discovery. I will be discussing details of Dr. Banting’s process.

If you’d rather not read the details, that’s completely understandable. You might be interested in the children’s graphic novel “Fred and Marjorie: A Doctor, A Dog, and the Discovery of Insulin” instead. It was written for children 8 and older and is a great way to understand the role that dogs played in the discovery, without all of the potentially disturbing details.

Now, I’ll go ahead and jump into it.

May 27, 1921 – Research begins

Banting and Best had a plan. They were going to use dogs for their research. John Macleod provided a research lab and 10 dogs to experiment on.

Some of the dogs were to have their pancreases removed to cause diabetes. Others were to have their pancreases ligated. The expectation was that they could cause the pancreas to degenerate and then they’d be able to extract the secretion (insulin). This secretion would be injected into the dogs whose pancreases had been removed.

Unfortunately, Banting was not very familiar with animal surgery. 7 of the 10 dogs had passed away during surgery or from infections by the end of the second week.

No more dogs were provided from the lab. Banting and Best started purchasing dogs off the streets of Toronto for $1-3 each.

Disappointment and discouragement

Banting had ligated the pancreases of 7 new dogs. In early July, he opened the dogs back up to see if their pancreases had degenerated.

To his dismay, he found that the catgut he had used to ligate the pancreases had loosened and only 2 of the 7 dogs pancreases had degenerated. He re-ligated the other 5 dogs with silk.

Two of those five dogs passed away the next day from complications.

Another two of the dogs who had their pancreases removed died from infections.

The researchers were very discouraged and took the long weekend to regroup.

July 27th, 1921 – Dogs 391 and 410

Finally, on July 27th, the researchers had 1 dog without a pancreas (Dog 410) and one whose pancreas had been successfully ligated (Dog 391).

On July 30th, Banting took Dog 391’s pancreas and froze it in a solution similar to saline. Then they ground it onto a paste, filtered it, and brought it back to room temperature. 4cc of the extract was injected into Dog 410.

They quickly saw results! Dog 410’s blood glucose went from 0.20% down to 0.12% in an hour. Non-diabetic dogs that they had tested had an average blood glucose of 0.09%.

Although hourly injections were given to Dog 410, its blood glucose did not decrease any further. The next morning, Dog 410 was found in a coma and soon passed away.

Dog 410 was the first test subject to receive the extract. Although he had died, the blood glucose results were promising. Banting and Best were on the right track!

Dog 408

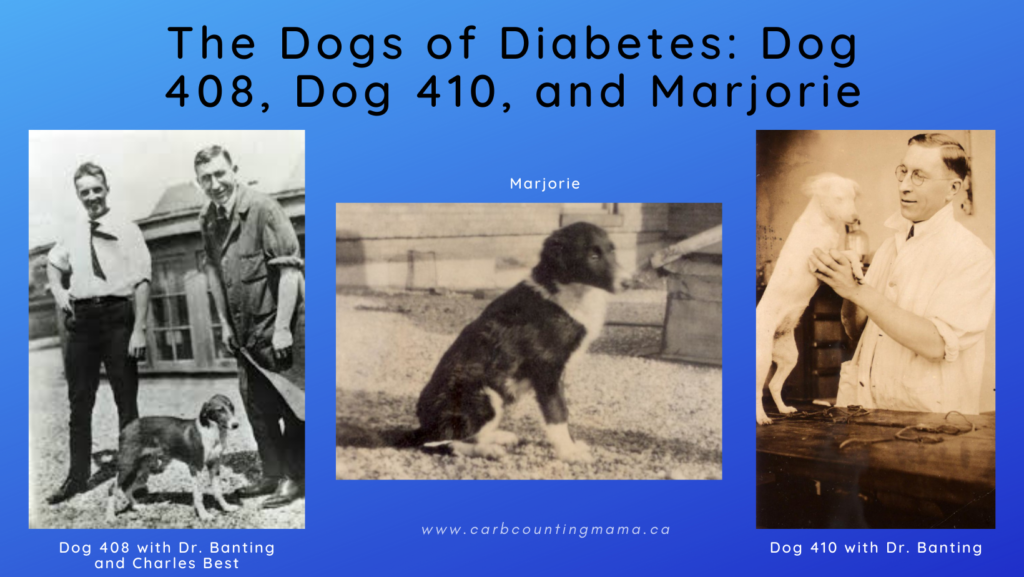

Dog 408 was a collie. One of the most famous pictures of Banting and Best is with Dog 408 on the roof of the University of Toronto’s Medical Building. The dog in that image is often mistakenly said to be Marjorie, but the Banting House National Historic Site of Canada has confirmed that it’s actually Dog 408.

Banting and Best removed Dog 408’s pancreas and started experimenting on August 3rd, 1921.

The experiments lasted 4 days. Banting and Best performed control experiments using extracts from the liver and spleen and also experimented with “isletin”, the term Banting used early on that eventually transformed into “insulin”.

The isletin experiment was successful. Dog 408’s blood sugar levels were dropping. After receiving 5cc of isletin, Dog 408’s blood glucose dropped from 0.26% to 0.16% in 35 minutes. You can even view a chart showing the sugar levels in Dog 408’s blood and urine, written by Dr. Banting.

Unfortunately, Dog 408 passed away from infection and shock on the 4th day. But Banting and Best were getting excited and sent Macleod a report of their findings.

Dog 92 and new approaches

While waiting to hear back from Macleod, Banting and Best continued with their experiments.

On August 11th, Banting and Best started another round of experiments. This time they used 2 dogs. Dog 92 and Dog 409 had their pancreases removed. Dog 92 was to receive the extract. They compared the results with Dog 409 who received no extract.

Of course, Dog 409’s condition steadily declined, and it soon died.

But for Dog 92, the extract worked quite well. He was described as “frisky” and became somewhat of a pet in the lab.

Banting and Best continued to refine their process.

Ligating the pancreases was time-consuming, and since they were using whole pancreases, there were toxic materials in the isletin. The isletin wasn’t pure and attempts to purify and concentrate it by boiling off the toxins also destroyed the isletin.

In an effort to produce more isletin, Dr. Banting tried a procedure to stimulate the pancreas using the hormone secretin. This process was time-consuming and complex.

On August 20th, Dog 92 was injected with the new extract. At first, he got sick, but he was back to his usual self the next day.

Dr. Banting continued with his experiments. He attempted to perform the secretin procedure on a cat pancreas and injected the extract into Dog 92. Dog 92 had a bad reaction to this extract and went into shock.

Experiments on Dog 92 stopped abruptly. The dog lived another 9 days, passing away on August 31st.

About Dog 92’s death, Banting said, “I have seen patients die and I have never shed a tear, but when that dog died, I wanted to be alone for the tears would fall despite anything I could do.”

The extract still had toxins and impurities

Since Banting and Best were using entire pancreases to procure the extract, isletin wasn’t the only hormone in there. While the isletin was helping to lower blood glucose levels, the other materials were causing infections and other negative reactions in the dogs.

On November 16th, Dr. Banting had an idea.

From working on his father’s farm as a child, he knew that farmers impregnated cows before they went to slaughter. This was done to make them gain weight, therefore making them worth more to the farmer.

The fetal pancreases wouldn’t have the digestive enzymes yet, as they didn’t have to digest anything. These pancreases should work better than the cat and dog pancreases that they had been using.

They procured fetal bovine pancreases and extracted isletin from them. This new extract was administered to Dog 27. The dog’s blood glucose dropped and after 24 hours, its urine was completely sugar-free.

The researchers kept modifying their technique. They started using adult bovine pancreases so that their isletin supply wouldn’t be as limited. Most importantly, they decided to use alcohol to prepare the extract, instead of a saline solution.

The saline extract couldn’t be concentrated as easily because, in order to concentrate it, they had to boil off the excess saline… which destroyed the isletin. Since alcohol evaporates at a lower temperature, it was easier to concentrate the extract this way.

Dog 33: Marjorie

On December 7, 1921, Banting used the new alcohol extracted isletin on Dog 33 (Marjorie) and Dog 23. The results were amazing.

Dr. James Collip joined the team on December 12, 1921. His biochemistry background allowed him to purify the extract even more.

Marjorie lived on isletin injections for 70 days! During that time, they started testing the extract on human subjects, starting with the famous case of Leonard Thompson.

On February 15, 1922, Marjorie was put down. She had developed abscesses at the injection sites and it was decided that the limited quantity of insulin should be used on human patients.

As mentioned at the beginning of this article, there is a lovely children’s graphic novel about “Fred and Marjorie: A Doctor, a Dog, and the Discovery of Insulin” if you’re interested in reading more about Dr. Banting and Marjorie.

The importance of the Dogs of Diabetes

As you may have noticed, the numbers that went with the dogs and the dates don’t correlate very well. I’m not sure how Banting and Best numbered their dogs, but I’ve read that there were 33 dogs in total from May to December 1921.

Their experiments simply would not be allowed today. Even in Banting’s time, vivisection was starting to be frowned upon and the researchers were worried about how their methods would be received by other scientists as well as the public.

While it is extremely sad that those dogs (and other animals) lost their lives, millions and millions of people are alive today because of the research that Banting and Best did, in a University lab, with next to no funding, and a whole lot of luck.

And for that, I’ll always be thankful for Banting, Best, Collip, Macleod, and the dogs of diabetes.

For more tips and stories about T1D, join the Carb Counting Mama email list, and make sure to head over to the Carb Counting Mama Facebook page and “like” it.

Leave a Reply