Bolus. It’s a simple term. I had never heard the word bolus before my son was diagnosed with T1D. It wasn’t long after that I learned what it meant. But for such a simple term, it can be a very complex action. It’s been over 6 years since my son was diagnosed and, to tell you the truth, I have come across yet another way to bolus (that I had never heard of before) just a few days ago.

(This article contains affiliate links. That means, if you purchase something through a link, I will make a commission at no extra cost to you.)

** This article is informational only and is not meant as medical advice. If you want to try something new with your diabetes care, please consult your diabetes specialist.

What is a bolus?

The actual word, the term “bolus” means, “A single, relatively large quantity of a substance, usually one intended for therapeutic use, such as a bolus dose of a drug injected intravenously.”

In the world of T1D, a bolus is not injected intravenously. It is a dose of insulin either given via syringe, pen, or pump, that is taken with food or to bring down a high blood glucose level.

** Check out the T1D Mod Squad Modipedia for a list of T1 terms and definitions!! **

Bolus vs Basal

When you have T1D, you have to take insulin. Something many people don’t learn (usually until they get an insulin pump) is the names of different kinds of insulin dosing. Whether or not you use a pump, you will have basal insulin and you will use bolus doses of insulin.

Basal is the background insulin. It is continuously working in the body to counteract glucose that is secreted by the liver. Its purpose is to keep blood glucose levels steady.

People on multiple daily injections (MDI) will use a long-acting insulin as their basal. Depending on the person and brand of insulin, this will be 1 or 2 injections a day.

People with insulin pumps use rapid-acting or ultra-rapid-acting insulin as their basal. Different basal levels can be set for different times of the day. A little bit of insulin is administered at set time intervals (generally every 5 minutes). Basal can be increased or decreased in pumps as needed.

Bolus is insulin used to counteract food or to bring down a high blood glucose level. Each dose is calculated and administered by the person with T1D or their caregiver.

Everyone uses rapid-acting or ultra-rapid-acting insulin to bolus. People on MDI get a new injection each time they bolus (at least 3 times a day, but can be much more). People using insulin pumps bolus the same number of times, but a small cannula is inserted under the skin to deliver the insulin so there is not a new poke each time a bolus is needed.

Meal/Snack Bolus vs Correction Bolus

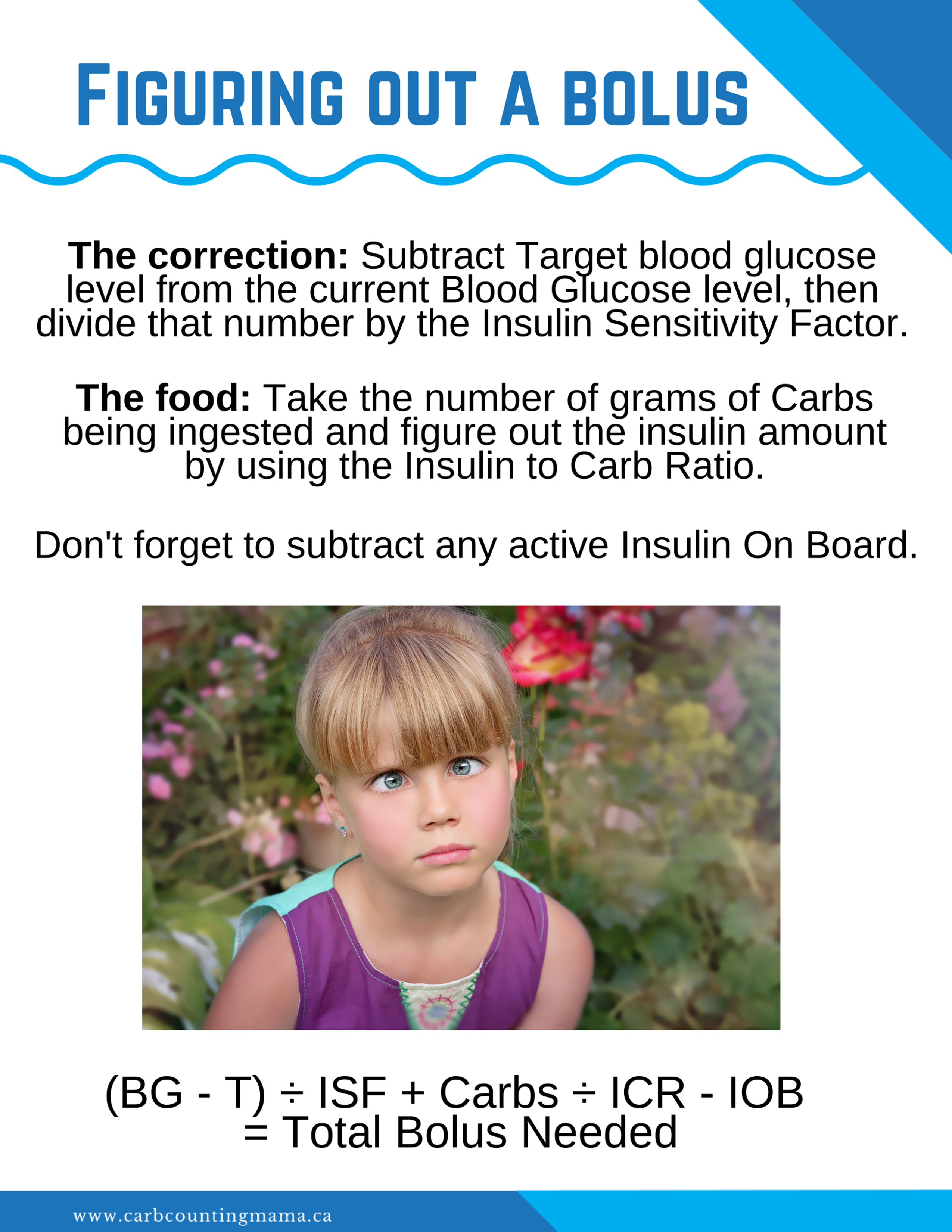

So, I’ve mentioned that there are 2 times you want to bolus. One is with food, the other is for high blood glucose. They each have their own calculations that go with them… math is fun.

The meal/snack bolus is generally just referred to as a bolus. Here’s how you figure it out. You’ll have an insulin to carb ratio (ICR). This ratio tells you that 1 unit of insulin will counteract X grams of carbs. The ratio is different for everyone and one person will likely even have different ratios at different times during the day.

Let’s say your ICR is 1:30. That means, for every 30g of carbs you eat, you need 1 unit of insulin. So, if you’re eating 45g of carbs, you need 1.5 units of insulin. Pretty easy right?

The correction bolus is generally referred to as a correction. The correction dose is calculated with the insulin sensitivity factor (ISF). This tells you that 1 unit of insulin will bring your blood glucose down by X. Like the ICR, the ISF is different for everyone and can change throughout the day. It will also look drastically different for people who use mmol/L to measure blood glucose levels vs people who use mg/dL.

For my son, here in Canada, an ISF might be 8. So, 1 unit of insulin would bring his blood glucose of 14.0mmol/L down to approximately 6.0mmol/L.

The same ISF in the US (and other countries who use mg/dL) would be 144. This would bring a blood glucose of 252mg/dL down to 108mg/dL.

Of course, if your blood glucose is high and you’re about to eat, you will combine these formulas to come up with one bolus amount.

Different ways to bolus

Ok, this is where it gets crazy.

Either at or shortly after diagnosis, you are taught how to bolus. Food gets 1 unit of insulin per X amount of carbs. 1 unit of insulin brings the blood sugar down by X. So, when you eat, you do a little formula and if your blood sugar is high, you do a different little formula. If you’re going to eat and your blood sugar is high, you combine the two formulas.

You calculate, you give insulin.

That’s the simple version.

Let me really drive this home with an image. THIS… is the simple version:

Once you get the hang of that, you start to realize that there are so many other ways to bolus. And that confusing formula… that’s nothing.

Pre-bolus

Pre-bolusing is a really great tool to help avoid post-meal spikes. All it means is that you bolus before eating.

Even rapid-acting insulin takes approximately 20 minutes to start working. So, the idea is to give the insulin prior to the meal. That way the food and insulin are processed in the body at roughly the same time.

Depending on your level of experience and comfort, you may use different timing with your pre-bolus.

For instance, if your blood sugar is high prior to eating, there is a rule of thumb to calculate pre-bolus timing. For mg/dL numbers, take the blood glucose number and remove the last digit. That’s how many minutes should be between the insulin dose and the meal.

Ex: If your blood glucose is 180mg/dL, bolus 18 minutes prior to eating.

This is a general guideline and is not right for every situation or for every person. It’s simply a good starting point.

If you have a Dexcom or other CGM device, another option is to bolus and “wait for the bend”. This technique is taught in Dr. Ponder’s book “Sugar Surfing“.

Post meal bolus

If insulin takes a while to work, why would you want to bolus post-meal?

Well, there are several reasons. The main ones are:

- Dealing with toddlers.

- Dealing with picky eaters.

In both of these situations, it’s hard to determine how much the child will eat. Giving the insulin and having them refuse to eat can be very dangerous. So, in those cases, it’s often considered safer to dose after the meal.

There are also situations like BBQ’s, potlucks, or large holiday dinners where you may not know how much you are going to eat. Sometimes, it’s a good idea to add everything up as you eat it and then bolus afterward.

Extended bolus

This one has different names depending on which device (if any) you’re using. For Medtronic it’s a “dual wave bolus”, for Animas it’s a “combo bolus” and for Omnipod it’s called an “extended bolus”.

The extended bolus is a bolus that is not given all at once. A percentage of the bolus is given up front (the percentage is determined by the user) and the remaining insulin is given over a set amount of time, usually a couple of hours.

This will often be used for meals that are high in carbs. Particularly if the food is high on the glycemic index. Foods like pasta, pizza, ice cream, and Chinese food, are higher in fat and take longer to break down in the body.

Since the insulin works at the same rate no matter what type of food you’re eating, this method breaks up the bolus so that it covers the breakdown of food more accurately.

Square wave bolus

A square wave bolus is specific to Medtronic pumps. It is very similar to an extended bolus. Instead of giving a portion of insulin up front, the square wave bolus evenly splits the entire bolus over a set period of time.

The use of a square wave bolus vs a dual wave bolus will depend on the person, their activity level prior to eating, what type of food they are eating, and several other factors.

Super bolus

The super bolus is used much less frequently than the other methods mentioned above. It is used for high carb foods that cause a spike (like cereal). It is calculated by adding basal to the bolus and then decreasing the basal.

For example, if you’re going to eat a bowl of cereal but don’t have time to pre-bolus, you could calculate your normal bolus, add on 2-3 hours worth of your usual basal rate, and reduce or turn off your basal for that time period. This helps avoid the spike because more insulin is being used up front, but it also doesn’t cause a low because the basal gets turned down.

Figuring out the timing and what percentage you want to use is a very individual thing. Some people keep their basal at 10 or 20% during a super bolus while others will turn it off completely. This trial and error is probably one of the reasons it’s not as widely used as the other techniques.

Split bolus and other MDI methods

What if you don’t use an insulin pump? There’s not much you can do to adjust the bolus for different foods… right?

Wrong.

It takes more pokes, but any bolusing technique used with a pump can also be done when you’re MDI.

Split bolus is like the extended bolus. You figure out the dose needed and instead of giving it all at once, you decide how much to give up front and give the rest at a later time (depending on the type of food etc). One thing to be very aware of is not forgetting to give the second bolus. Setting a reminder alarm is a great way to avoid this issue.

You can achieve an effect similar to the super bolus by giving a larger bolus up front and using carbs to “put the brakes on” (another Sugar Surfing technique). Because you are not able to reduce your basal on MDI, carbs are used instead. Just make sure you/ your child will have an appetite for more carbs as a super bolus is generally used for large, already carby meals.

When you’re MDI, there are other things you can figure out as well. A family I know pays a lot of attention to how different sites absorb insulin. They have figured out that if they dose partially in the leg and the rest in the tummy, it can work like an extended bolus because one site absorbs insulin significantly faster than the other. This sort of thing will be very individual. It may work well for some and not work at all for others.

Factors that may affect how you bolus

So, first we learn what a bolus is and use the basic formula(s) provided by our diabetes clinic.

Then, we start learning about different glycemic index foods (whether we learn the actual GI values or just see a trend with certain foods). Food is obviously one of the biggest factors to consider when bolusing. But there are many, many other factors that can be taken into consideration.

Activity

Being active can help to lower blood glucose levels. It is particularly effective when there is active insulin in your system. So, if you need to bolus shortly before activity, you may want to decrease the amount of insulin you’re going to use.

Likewise, if you have just been quite active, the insulin will seemingly work better and you may not need as much.

If you have a high blood glucose level and you’ve bolused recently, activity can sometimes be used to bring the level down rather than giving more insulin. We find trampolines and scooters do the trick nicely.

Temperature

When the body is warm, insulin tends to absorb easier. This is why insulin needs tend to decrease in the summer.

It’s also one of the reasons why warm/ hot baths, showers, and using hot tubs are not recommended for people with diabetes. If you’ve ever noticed a sudden blood glucose drop after dinner, around bath time, warm water could be the reason.

If you’re having a stubborn high blood glucose, you might consider taking a warm bath to help the insulin work.

Insulin resistance

Insulin resistance can come and go for various reasons. High blood glucose levels alone can cause insulin resistance. If you correct a number that is on the higher side of “in range”, it’s much easier to bring back down than a number that has gone high enough to be out of range.

Different hormones can also cause insulin resistance. Insulin is a hormone, so it is affected by other hormones. Growth spurts, menstruation, and puberty (among other things) can all cause problems with insulin absorption.

Ketones are another factor that causes insulin resistance. Ketones generally need extra insulin to get rid of them, so make sure you have a ketone dosing chart from your diabetes team in case you ever need to deal with ketones.

Cold or Flu

Illness is very dangerous for someone with T1D. Different illnesses will cause either insulin resistance or quicker insulin absorption. Being sick can also affect how your body breaks down and uses carbs.

So, as one can assume, it gets quite complicated when you get sick. There’s no way to know which way it will go until you either go high or low.

During an illness, you should use whatever protocol your diabetes team has given you. If you don’t have one, figure out what they want you to do. And if in doubt, go to the ER. Illnesses can turn into DKA very easily.

That’s a bolus

I didn’t know what “bolus” meant when my son was diagnosed with T1D. Now, I know more about that word than I ever cared to learn. I’m sure there is more that I have yet to come across.

Guess I was wrong about it being a simple term…

Happy Carb Counting!

~ Leah

Do you bolus in a way that wasn’t listed in this post? Tell me about it in the comments!!

For more tips and stories about T1D, join the Carb Counting Mama email list, and make sure to head over to the Carb Counting Mama Facebook page and “like” it.

Nicely done Leah 🙂